In this intimate interview, director Eugene Yi and producer Diane Quon share how they crafted “The Rose: Come Back to Me”. It’s a documentary capturing The Rose’s emotional journey, mental health battles, and ultimate comeback.

A Story That Walks Beside You

I didn’t expect to cry.

I wasn’t even aware it was happening until I felt the warmth on my cheeks, the credits rolling while my chest still felt full.

“The Rose: Come Back to Me” isn’t just a documentary you watch — it’s one you walk through, side by side with Woosung (Sammy), Dojoon (Leo), Taegyoem (Jeff) and Hajoon (Dylan).

The editing is masterfully deliberate. Director Eugene Yi and producer Diane Quon don’t simply present a timeline; they invite you to inhabit the moments:

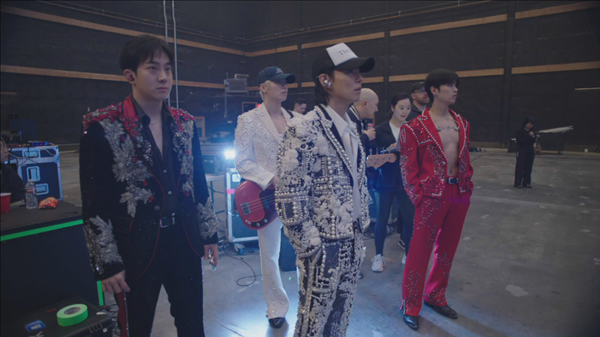

The rush of a festival crowd.

The stillness of a backstage corridor.

The ache of separation during the band’s hiatus.

The film moves like memory itself — quick flashes of joy, weighty beats of doubt, and sudden swerves when you’re not sure what’s next. Somewhere between the street-busking footage and the Coachella stage, their story becomes a mirror.

As a viewer, I felt the happiness, fear, and uncertainty that shaped their journey. . It became a mirror. In their uncertainty, I saw my own.

Interview with Director Eugene Yi and Producer Diane Quon

How did the idea for this film come about?

Diane Quon: It started with a conversation. Janet Yang, our executive producer, was speaking with her friend James Roh from Transparent Arts, who had just signed The Rose. James shared their story — four young men who had walked away from the K-pop training system to form a band on their own terms. Janet told me, and I was immediately drawn in. I love stories of young people refusing to be boxed in, determined to do things their way.

Why The Rose? What drew you to their story?

Eugene Yi: I’ve always been fascinated by Korean rock, which has never been mainstream in South Korea during my lifetime. The Rose lives at a crossroads — they come from the K-pop system but chose to step outside it, forging something new. They didn’t just choose each other as bandmates; they chose healing as a central theme in their music. That’s rare.

The film feels like a reclamation of identity, not just a comeback. How did you balance the struggles with the joy?

Diane Quon: All four of them expressed the will to be real, to be transparent. They wanted to tell their story unfiltered. That came through in each of my individual conversations with Sammy, Leo, Jeff and Dylan. That’s when I knew they were willing to open up.

Eugene Yi: That balance came from honesty. We didn’t shy away from the pain — lawsuits, mental health struggles, years apart. But we also let the joy be as big as it deserved to be: the roar of the crowd, the quiet moments of connection, the sheer relief of creating freely again.

Mental health and healing are central to The Rose’s message. Was there a moment where this theme became deeply personal for you?

Eugene Yi: The candor with which they spoke about mental health really struck me. In Korea, the conversation is still growing, and they weren’t just willing — they were eager — to talk openly. Hearing them speak with that vulnerability, knowing their fans would see it, was when I realized the film could be more than a chronicle of a band. It could be part of a cultural shift.

The Rose comes across as both artists and individuals in the film. How did you earn their trust?

Diane Quon: Trust took time. Our first Zoom meetings were about listening, not pitching. We needed them to see we weren’t there to exploit their struggles, but to honor their truth. We filmed with the same small crew over several months. As we travelled with them, filmed backstage, and stayed present in quieter moments, that trust deepened. Eventually, they let us into the spaces where the real conversations happen — and the cameras became invisible.

The Black Roses, their fans, are a global force. Would you call this film a love letter to them?

Diane Quon: The fans carried the band through the dark years, and the guys know it. You can feel the reciprocity — every show is like an ongoing dialogue between them and the Black Roses.

Eugene Yi: Everything they do, they keep their fans in mind. When they write music or plan a show, they think about what will connect. We wanted to give Black Roses something they didn’t already know about the band — to surprise them, not just confirm what they expected.

The band’s journey spans street busking, lawsuits, military service, and Coachella. What was the biggest narrative challenge?

Eugene Yi: The sheer scope — four separate protagonists, a sprawling timeline, and wildly different settings from Seoul’s streets to Coachella’s desert stage. Some material emerged faster than I anticipated, like Jeff’s story. Thanks to his openness, his segment came together fast. Our editor shaped it so the threads wove into one story: not just what happened, but why it mattered.

The collaboration with Transparent Arts adds another dimension. How did that shape the story?

Eugene Yi: Transparent Arts, (founded by Far East Movement NA), knows what it’s like to break barriers as Asian American artists. Their relationship with The Rose is about more than business — it’s mentorship, shared history, and mutual trust. Watching those conversations play out, across continents and generations, gave the film a deeper heartbeat.

What surprised you most about what the band was willing to share?

Diane Quon: Their openness. I expected some things to be off-limits. But they spoke frankly about burnout, doubt, and the weight of expectations. That vulnerability wasn’t just brave — it was intentional. They know sharing it might help someone else feel less alone. We all go through painful moments. The pain may stay, but we build the strength to carry it.

Was there a moment when you thought, “This is why we’re making this”?

Eugene Yi: Seeing them at Coachella. A Korean indie rock band, not backed by a major label, standing on that stage — that’s not a typical trajectory. It was proof that forging your own path can take you further than you might imagine.

Were you ever concerned their being forthcoming could be misunderstood, especially back home in South Korea?

Diane Quon: I considered that. I never want anyone to be harmed by the work we do. But they were adamant about being real. All four vowed — and proved — to be completely transparent.

Eugene Yi: Hiding or omitting was never an option. They wanted to tell their stories on their own terms, with their own words. That was enough to remove any doubt or fear we might have had.

What do you want audiences to take away from the film?

Eugene Yi: They wrote a song for the documentary while we were filming — “Trauma” — and it sums up the whole film. I hope people take away the freedom to tell their own story and the strength to face their own trauma, whatever that may be.

After the Credits

By the time the final scenes rolled, I realized I’d been holding my breath.

“The Rose: Come Back to Me” is a documentary about a band overcoming obstacles as well as a meditation on how joy and doubt, fear and hope, often live side by side.

For me, the film’s greatest strength is how it draws you into those emotional shifts until they become your own. The Rose’s raw honesty becomes an invitation to look at your own hesitations, to acknowledge them, and to still move forward. And it’s truly okay not to be okay.

Maybe that’s why the tears came without warning. This wasn’t just a story about a band coming back. It was about the possibility of coming back to yourself.

It was my very own She’s in the Rain moment. And like the band’s music, it leaves you with the quiet conviction that healing is something we do best together.

Connect with the author Maggie A. R. on LinkedIn

Join us on Kpoppost’s Instagram, Threads, Facebook, X, Telegram channel, WhatsApp Channel and Discord server for discussions. And follow Kpoppost’s Google News for more Korean entertainment news and updates.